Introduction to Artificial Intelligence

A comprehensive introduction to core AI techniques, completed with near-perfect marks. The project explores foundational methods such as evolutionary algorithms, supervised learning, and neural network training.

From Zero to AI: A Journey Through Algorithms, Experiments, and Surprising Discoveries#

Artificial Intelligence rarely starts with robots, neural networks, or “real” intelligence. It usually begins with something humbler-like a board game, a branching tree, or a handful of numbers fed into a mysterious black box called “the perceptron.”

A journey through several classical AI techniques-each different, each strange in its own way-and how they gradually build intuition for what intelligence actually means in computation.

When Intelligence Meets Calculus: Steepest Descent#

Before neural networks came into the picture, we took a detour into the world of optimization-the quiet engine behind much of modern AI. The idea was simple:

If you know the slope of a function, you can walk downhill until you reach the minimum.

This is the essence of Steepest Descent (a.k.a. Gradient Descent). We applied it to approximate a target function and observed how the algorithm behaves under different learning rates.

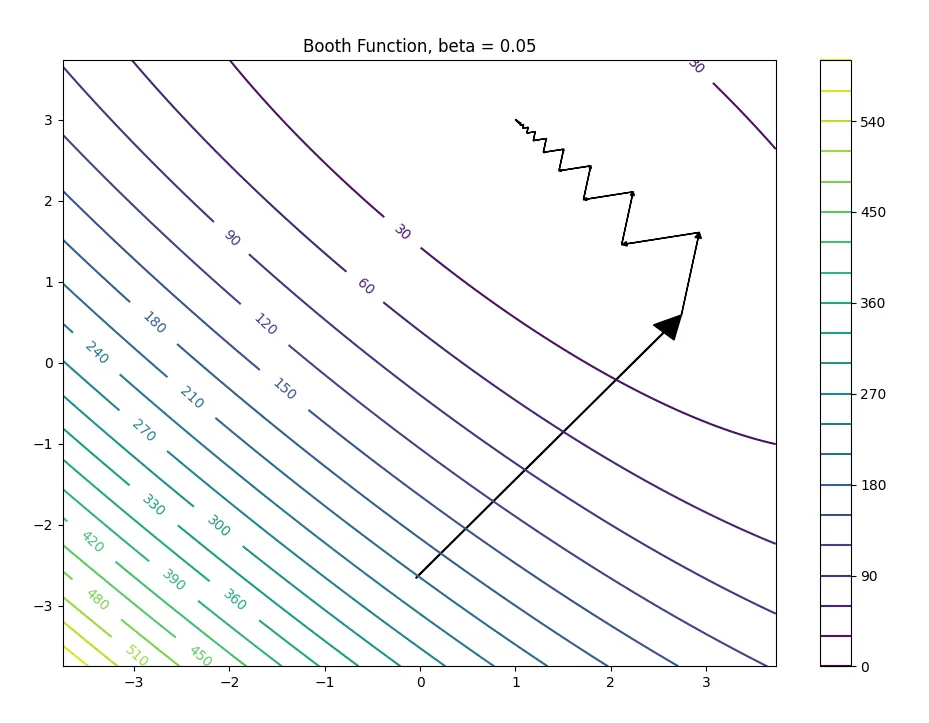

Gentle learning rate - steady but slow#

The first plot below shows the trajectory with a small learning rate. The descent is smooth and stable, slowly curving toward the optimum.

Aggressive learning rate - oscillations and chaos#

But when we increased the step size, something dramatic happened: Instead of converging, the algorithm overshot, bounced around, and sometimes diverged completely.

This experiment taught an important lesson:

Optimization is not just about going downhill-it’s about choosing the right size of each step.

This insight later became essential when we started training neural networks.

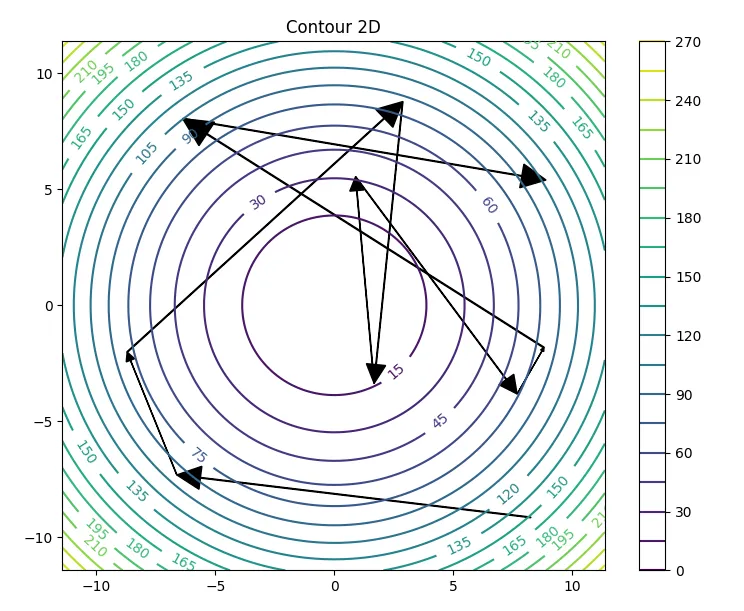

Teaching Evolution: A Simple Evolutionary Algorithm#

Before we trusted neural networks or reinforcement learning, we built something more primal- an evolutionary algorithm, inspired by biological evolution.

It worked in stages:

1. Initialization#

Generate a population of random candidate solutions.

population = [random_solution() for _ in range(N)]2. Evaluation#

Each solution receives a fitness score, measuring how close it is to our goal.

3. Selection#

We used tournament selection-strong individuals have a higher chance of reproducing, but weaker ones sometimes slip through to maintain diversity.

4. Crossover#

Two parents combine their “genes” to create offspring:

child[i] = parent1[i] if rand() < 0.5 else parent2[i]5. Mutation#

To avoid stagnation, a small random perturbation is applied:

if rand() < mutation_rate: child[i] += normal(0, sigma)6. Replacement#

The weakest individuals are removed, making room for new candidates.

What we learned from evolution#

The algorithm didn’t rely on gradients, differentiability, or structured models. It simply explored, adapted, and survived.

When parameters were tuned well, evolution produced surprisingly strong solutions- sometimes beating gradient-based methods when the landscape was rough or discontinuous.

Lesson: Evolution is slow but incredibly flexible. It shines when nothing else can find a way forward.

When AI First Learned to Play: Minimax and Its Flaws#

Our story starts with a simple task:

Teach a computer to play checkers.

Not modern checkers, though-our simplified version had:

- no mandatory captures,

- no multi-jumps,

- pawns moving only forward,

- kings moving any direction.

The twist? Captures weren’t required, so a human player would obviously grab an easy win when possible. But would an AI? That depended on its evaluation function.

Teaching the AI to “prefer” good moves#

We wrote several evaluators:

def evaluate_basic(board): # +1 for pawn, +10 for kingdef evaluate_version_2(board): # rewards pieces depending on their position on the boarddef evaluate_version_3(board): # rewards advancing toward the enemy halfand even a chaotic one:

def evaluate_random(board): return randint(-100, 100)Then we implemented:

- Minimax

- Minimax with Alpha-Beta Pruning

Suddenly, the AI started thinking-searching through future positions, choosing moves based on maximizing expected value.

But something strange happened#

Sometimes it behaved dumb.

It would:

- ignore easy captures,

- repeat moves in cycles,

- prefer “future king potential” over obvious tactical blows.

The reason? AI doesn’t think like humans-it optimizes whatever number you give it. If becoming a king is worth +10 and capturing a pawn is +1, the AI will walk past a free pawn like a dog ignoring kibble because someone offered steak.

What depth taught us#

Increasing search depth drastically improved play-up to a point. Here’s a snapshot from the depth-vs-wins table:

| blue\white | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | blue | white | white | white | draw |

| 5 | blue | draw | white | white | draw |

The lesson was simple:

AI is only as smart as the depth it can see. And search depth is expensive.

We had just discovered one of the oldest truths in AI.

Teaching Machines to Ask Questions: ID3 Decision Trees#

The next stop on our journey was the ID3 algorithm, a classic from the early days of machine learning.

This time, instead of moves on a board, our AI made questions.

At every split, the algorithm asks:

“Which attribute gives me the most information about the class?”

This is literally what we coded:

def entropy(class_counter): return -sum(count/total * log(count/total) ...)def information_gain(attribute, data, class_counter): return entropy(class_counter) - inf(attribute, data)def id3(data, attributes): # picks attribute with max information gainSuddenly our machine wasn’t searching or optimizing-it was learning patterns from examples.

Results that surprised us#

On the Mushroom dataset, accuracy was perfect:

| Dataset | Mean Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Mushroom | 100% |

| Breast Cancer | ~64% |

Why? Because mushrooms have highly discriminative attributes and breast cancer is messy, noisy, and ambiguous.

Lesson: Decision Trees shine when data is clean and categorical. They struggle when real-world ambiguity kicks in.

And just like that, we saw how data quality shapes AI performance.

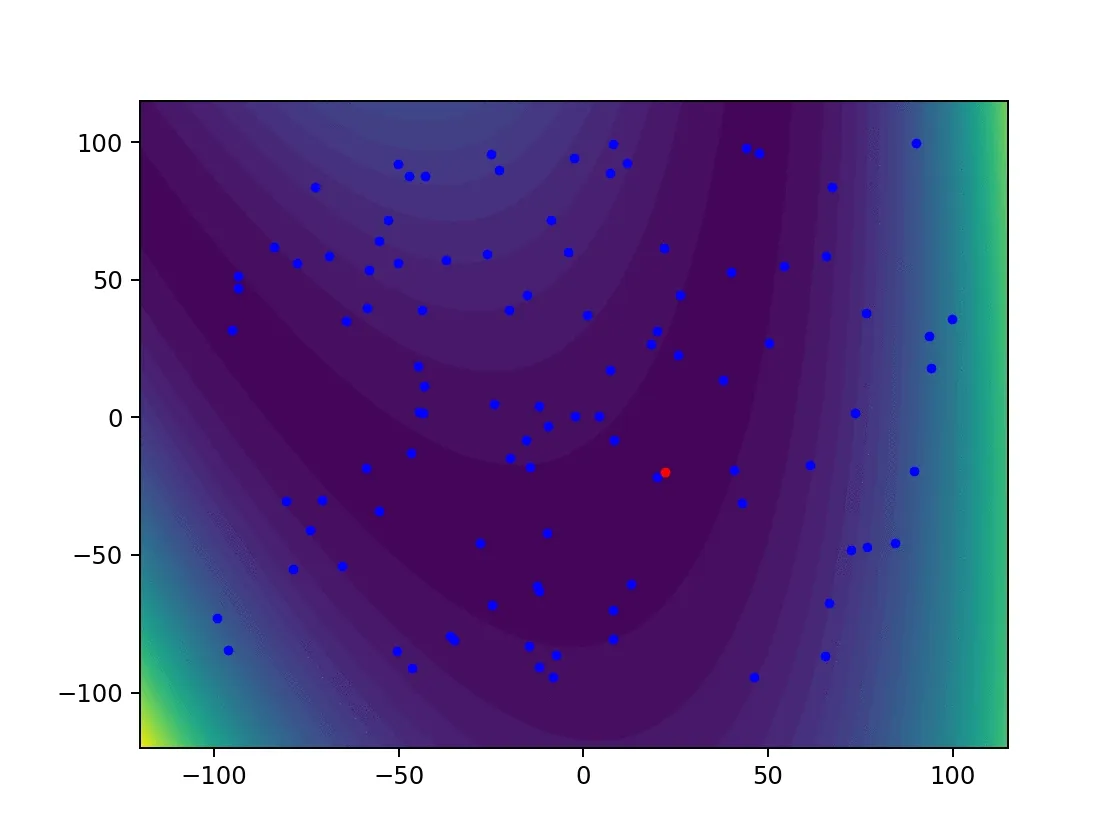

When AI Became a Function Approximator: The Perceptron#

Then the course shifted gears: From logical decision-making → to continuous approximation.

We implemented a two-layer perceptron to approximate:

$$ J(x) = \sin(x \sqrt{p_0+1}) + \cos(x \sqrt{p_1+1}) $$

Suddenly, the problems became more subtle:

- How many neurons do we need?

- How fast should the network learn (learning rate)?

- How big should the mini-batches be?

After dozens of experiments, we found the “sweet spot”:

hidden_neurons = 13epochs = 5000mini_batch_size = 100learning_rate = 0.1If we chose:

- Too few neurons → poor approximation

- Too many → overfitting

- Too low learning rate → slow convergence

- Too high → chaos

Neural networks are sensitive. Their learning process feels less like engineering and more like tuning a musical instrument.

Lesson: Neural networks don’t give intelligence for free. They require careful design.

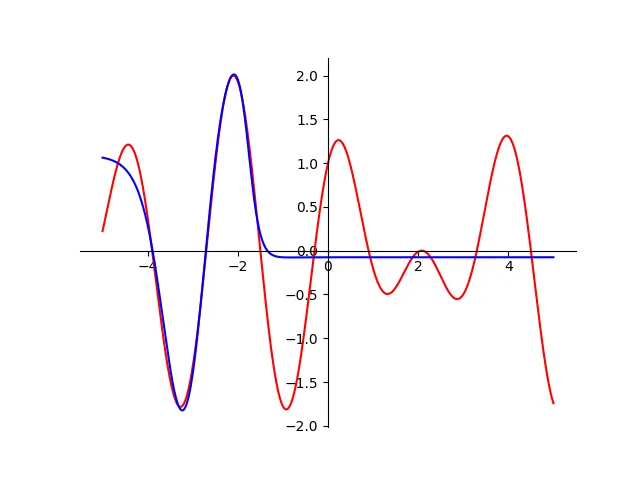

1. Underfitted Network - Too Few Neurons#

A neural network with only 1 or 3 neurons in the hidden layer simply couldn’t capture the complexity of the target function. The approximation was smooth but wrong-the model lacked expressive power.

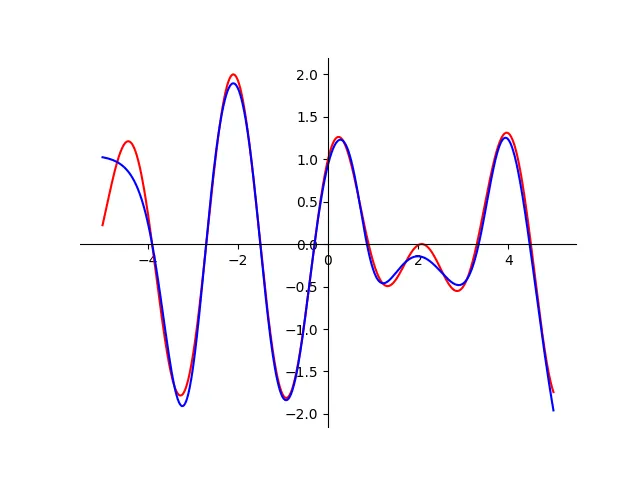

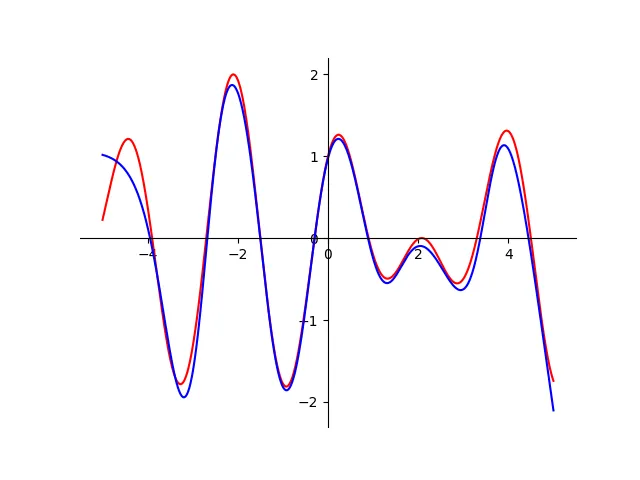

2. Ideal Capacity - Around 9-13 Neurons#

This configuration produced excellent results. The approximation hugged the target curve almost perfectly and trained efficiently.

3. Overfitting - Too Many Neurons (50)#

With an excessively large hidden layer, the network began learning noise. Instead of a smooth curve, we saw unnecessary oscillations.

The bigger picture#

By seeing these three examples side by side, the core idea becomes obvious:

Neural networks are powerful, but architecture matters- too small, and they’re blind; too big, and they hallucinate.

And training them successfully requires balancing:

- capacity

- learning rate

- batch size

- number of epochs

This is why the steepest descent and evolutionary algorithm chapters were so valuable - they taught us how to think about optimization before diving into neural models.

When AI Learned to Solve Mazes: Q-Learning#

Finally came reinforcement learning: Teaching an agent to navigate a slippery, hazardous FrozenLake8x8 environment.

The rule was simple:

AI learns by trial, error, and reward.

We implemented classic Q-Learning:

q[state][action] = q + lr*(reward + gamma*max(q[next]) - q)And tested different reward systems:

Reward system comparisons#

| Reward Scheme | Success Rate (avg) |

|---|---|

| +1 / 0 | ~67% |

| +1 / -1 | ~83% |

| +10 / -1 | ~82-84% |

Striking finding:

Penalizing failure improves learning more than rewarding success.

This aligns with behavior in nature: Avoiding danger is often more important than seeking reward.

Probabilities, Uncertainty, and Bayesian Networks#

The last step of our journey explored Bayesian Networks. Instead of deterministic rules or rewards, we now modeled probabilistic relationships.

We generated synthetic datasets:

generate_data(variables, filepath="generated_data.csv")And then used ID3 to classify things like “Ache” based on “Sport” or “Chair”:

Example frequency table:

| Variable | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Chair | 0.8015 |

| Sport | 0.0200 |

| Ache | 0.2058 |

Accuracy#

- ID3 achieved ~87% accuracy on generated data.

It wasn’t perfect-but it understood the probabilistic structure well enough.

Conclusion - What This Journey Teaches About AI#

By the end of these exercises, one thing becomes clear: There’s no single “AI.” There are many ways to make a machine act intelligently - and each reflects a different philosophy.

What we learned about intelligence:#

- Minimax taught us that intelligence can be brute-force search.

- Evaluation functions taught us that the definition of good behavior matters.

- Decision trees taught us that intelligence can be pattern recognition.

- Neural networks taught us that machines can approximate continuous worlds.

- Q-Learning taught us that intelligence can emerge from trial and error.

- Bayesian networks taught us how machines reason under uncertainty.

Put together, they reveal a bigger truth:

AI isn’t magic. It’s a toolbox. And every tool shapes the kind of “intelligence” we build.

This journey - from simple checkers to probabilistic reasoning - mirrors the history of the field itself. Starting with symbolic logic, moving to data-driven methods, and finally exploring learning through interaction.

And though these exercises were small, the ideas behind them power everything from recommendation systems to self-driving cars.