Universal Chessboard Bot

Engineered a full-stack generalized board-game AI project that implements and rigorously compares several advanced decision-making algorithms across multiple games and rule sets, not limited to standard chess. The work includes in-depth analysis of algorithmic complexity, practical performance, and gameplay strength. The solution integrates Java, Kotlin and the Deep Java Library (DJL) for core AI logic and leverages Apache Spark/PySpark for large-scale data analysis and evaluation of search and evaluation techniques. The project culminated in a fully playable Android application that allows users to compete against a strong computer opponent across supported games and variants.

Project Overview#

This thesis project presents a comparative study of decision-making algorithms for deterministic, zero-sum board games such as chess and checkers. The work includes:

- A universal rule-verifying engine supporting multiple board games

- A suite of AI bots implementing classical and modern search algorithms

- A performance study across 12 controlled configurations

- A final integration with an Android mobile application, allowing users to play locally against the evaluated bots

The system is designed to operate under varying computational constraints-including mobile devices-and evaluates how different algorithms behave in resource-limited environments.

Universal Chessboard Game Engine#

This repository implements a flexible engine capable of running a wide range of finite, deterministic, zero-sum board games. Its main focus is on chess and checkers, but the internal representation supports arbitrary chessboard-based rule sets.

The engine includes:

- A rule validator (originating from earlier engineering work)

- A modular search framework with multiple interchangeable components

- Game analysis tools, a match-maker, and a partial UCI protocol implementation

- Optional integration with external systems such as Lichess bots

Core Features#

Search Algorithms#

- Minimax

- Minimax + Alpha-Beta

- Principal Variation Search (PVS)

- Scout

- Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) + variants (Alpha-Beta, Best-First Minmax, Neural Network-based)

- Best-First Minimax

- Quiescence Search

Optimizations#

- Iterative Deepening

- Aspiration Windows

- Move Ordering Heuristics

- Transposition Tables (lockless, hash-based)

- Selective Extensions

- Parallel Minimax, Alpha-Beta, PVS, and MCTS (YBWC, Jamboree, PV-Splitting)

Board Representation#

- Bitboards

- Magic Bitboards for sliding pieces

- Static Exchange Evaluation

- Optimized legal move generator

Evaluation Functions#

- Material evaluation

- Piece-Square Tables

- Quiescence Search

- Experimental neural network evaluator (incrementally updatable)

UCI Support#

- FEN, startpos, custom move sequences

- Search configuration (depth, time, nodes)

- Engine options (threads, ponder, clear hash)

- Reporting (PV, score, NPS, time, depth)

Research Methodology#

The goal of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of different decision-making algorithms in deterministic, zero-sum board games. In particular, the research focused on:

- Assessing the quality of moves produced by various algorithms

- Identifying optimizations suitable for resource-constrained environments (e.g., mobile devices)

- Understanding trade-offs between algorithmic complexity and practical performance

Key Research Questions#

- Which decision-making algorithms are most suitable for chess-playing bots?

- Which modifications of classical algorithms (Alpha-Beta, MCTS, etc.) improve performance without significantly lowering move quality?

Experimental Setup#

To ensure reproducibility, the system uses 12 test configurations, each isolating a single algorithmic aspect. Every configuration keeps all parameters fixed except one-the component under evaluation.

Controlled variables include:

- Game types: Chess, checkers, mini-chess (5×5 board)

- Time limits per move: [100 ms - 2 s]

- Randomized starting positions: Each test position is played twice with swapped colors

- Search strategies: Depth-first (Minimax, Alpha-Beta, PVS, Scout), Best-First (MCTS, SSS*, BF-Minimax), and parallel variants

- Evaluation heuristics: Material evaluation, piece-square tables, quiescence search

- Transposition tables: Enabled/disabled to study their effect

- Aspiration windows: None, narrow, or adaptive

- Search extensions: Promotions, forced replies, and other selective deepening rules

This design made it possible to attribute performance changes to a single factor, ensuring clarity in the results.

Tournament Configurations#

@Getter@RequiredArgsConstructorpublic enum TournamentConfiguration { ALL, POSITION_EVALUATORS, TRANSPOSITION_TABLES, ASPIRATION_WINDOWS, MOVE_EXTENSIONS, COMPLEX_POSITION_EVALUATORS,

DEPTH_FIRST, DEPTH_FIRST_PARALLEL,

BEST_FIRST, BEST_FIRST_PARALLEL,

BEST_OF_ALL, BEST_OF_ALL_PARALLEL, ;}Research Findings#

1. Best Algorithms for Chess#

The experiments show that depth-first zero-window algorithms-especially PVS and Scout-consistently outperform:

- classical Minimax,

- Alpha-Beta alone,

- Monte Carlo-based methods,

- and Best-First Minimax variants.

Their advantage comes from aggressive pruning, which reduces the branching factor while preserving search depth where it matters most.

These methods performed best across:

- Chess

- Mini-chess

- Checkers

- Short and long time limits

2. Effective Modifications to Classical Algorithms#

Two optimizations stood out as high-impact and low-complexity:

-

Transposition Tables: Prevent redundant re-searching of already evaluated positions.

-

Quiescence Search: Prevents evaluating “noisy” tactical positions too early.

Both yield significant improvements in both win rate and stability.

More complex techniques-dynamic extensions, aspiration windows-require careful tuning and are game-dependent. They provide gains only under specific conditions.

3. MCTS Observations#

MCTS underperforms in chess-like games due to:

- Low-quality random simulations

- Difficulty capturing long-term positional strategy

- Limited time per move

However, performance improves when:

- Simulations use lightweight heuristics instead of random playouts

- Parallelization is available

- The domain has a lower branching factor than chess

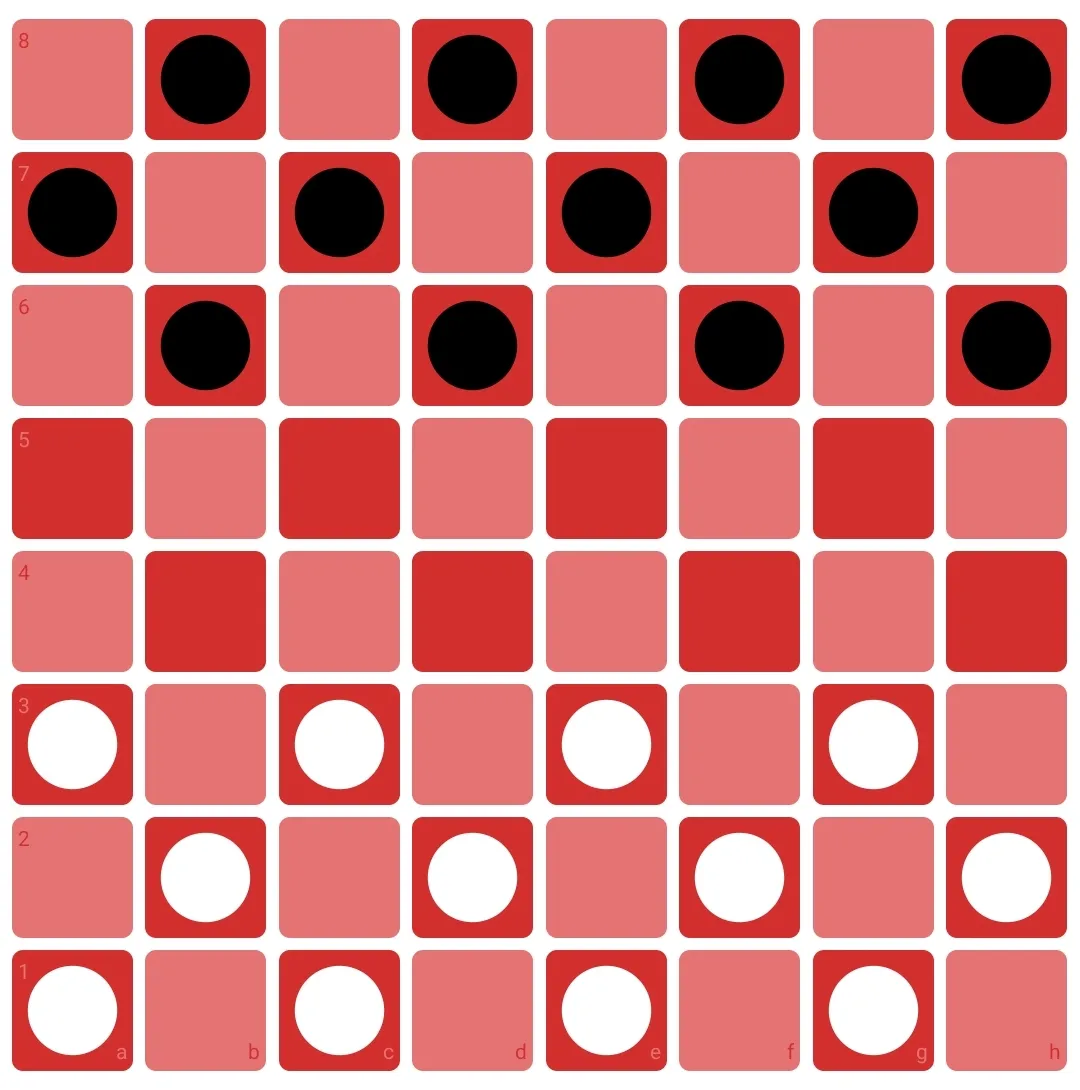

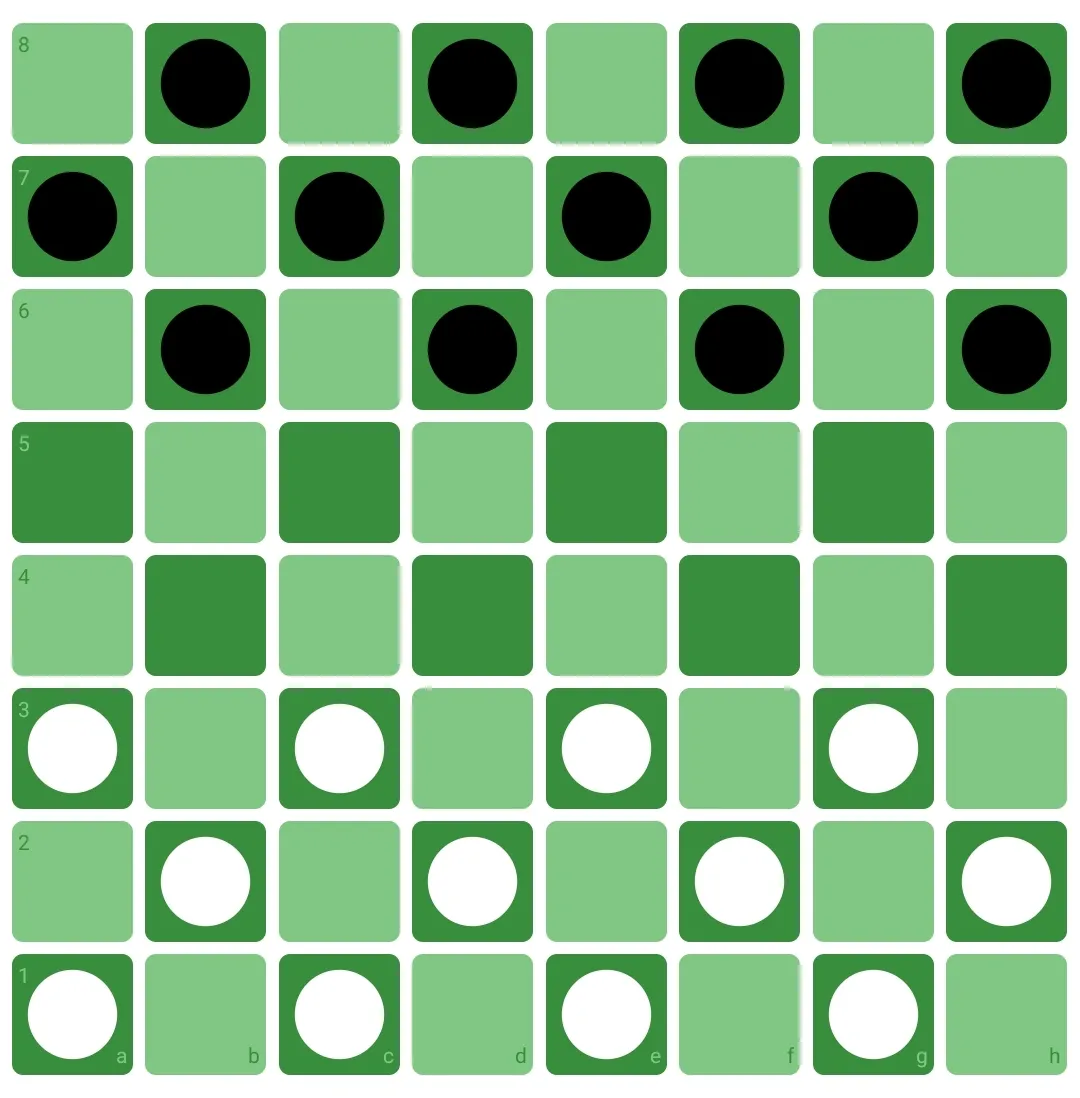

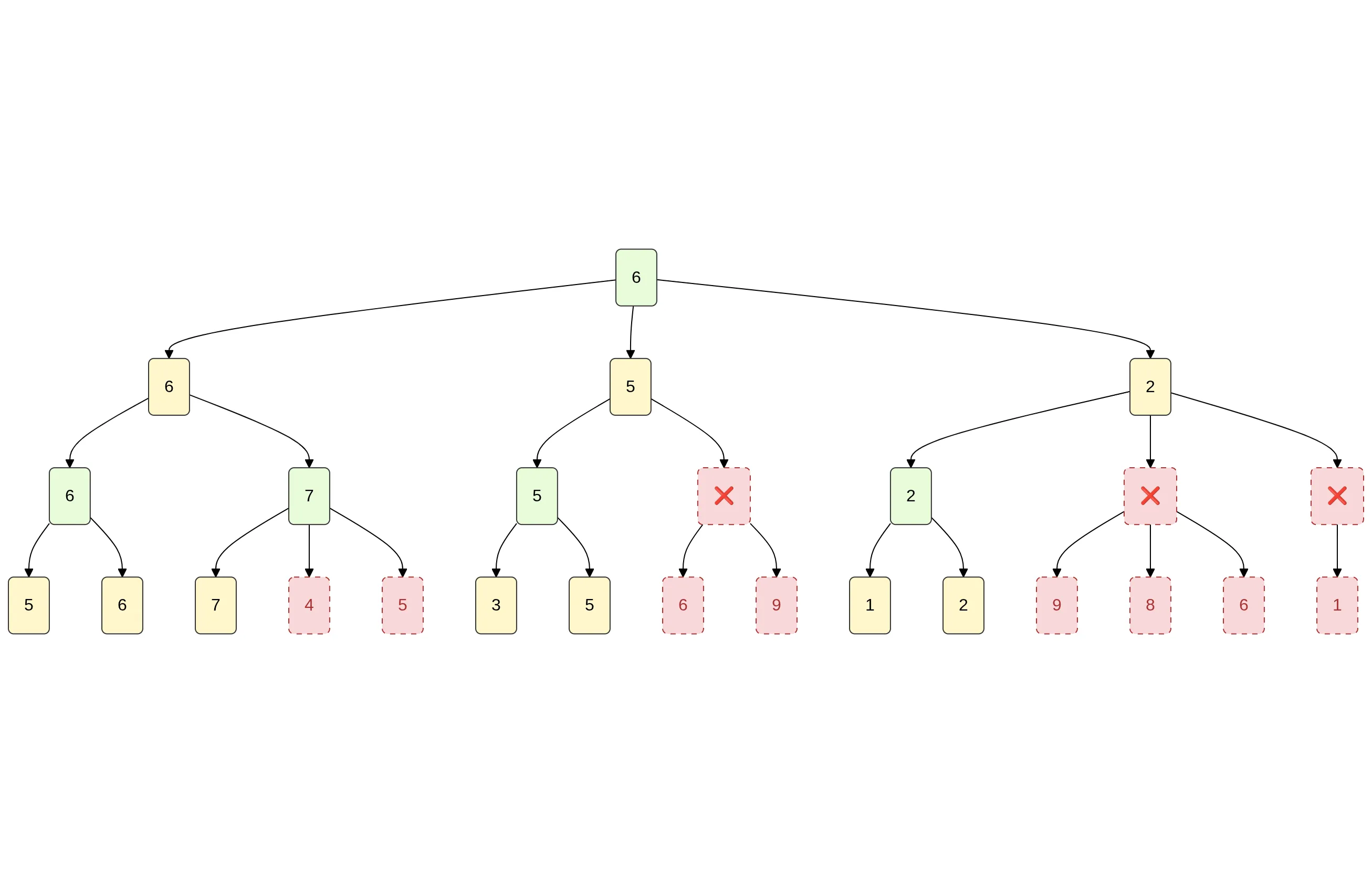

Algorithm types - examples#

Depth-First Search - Minimax#

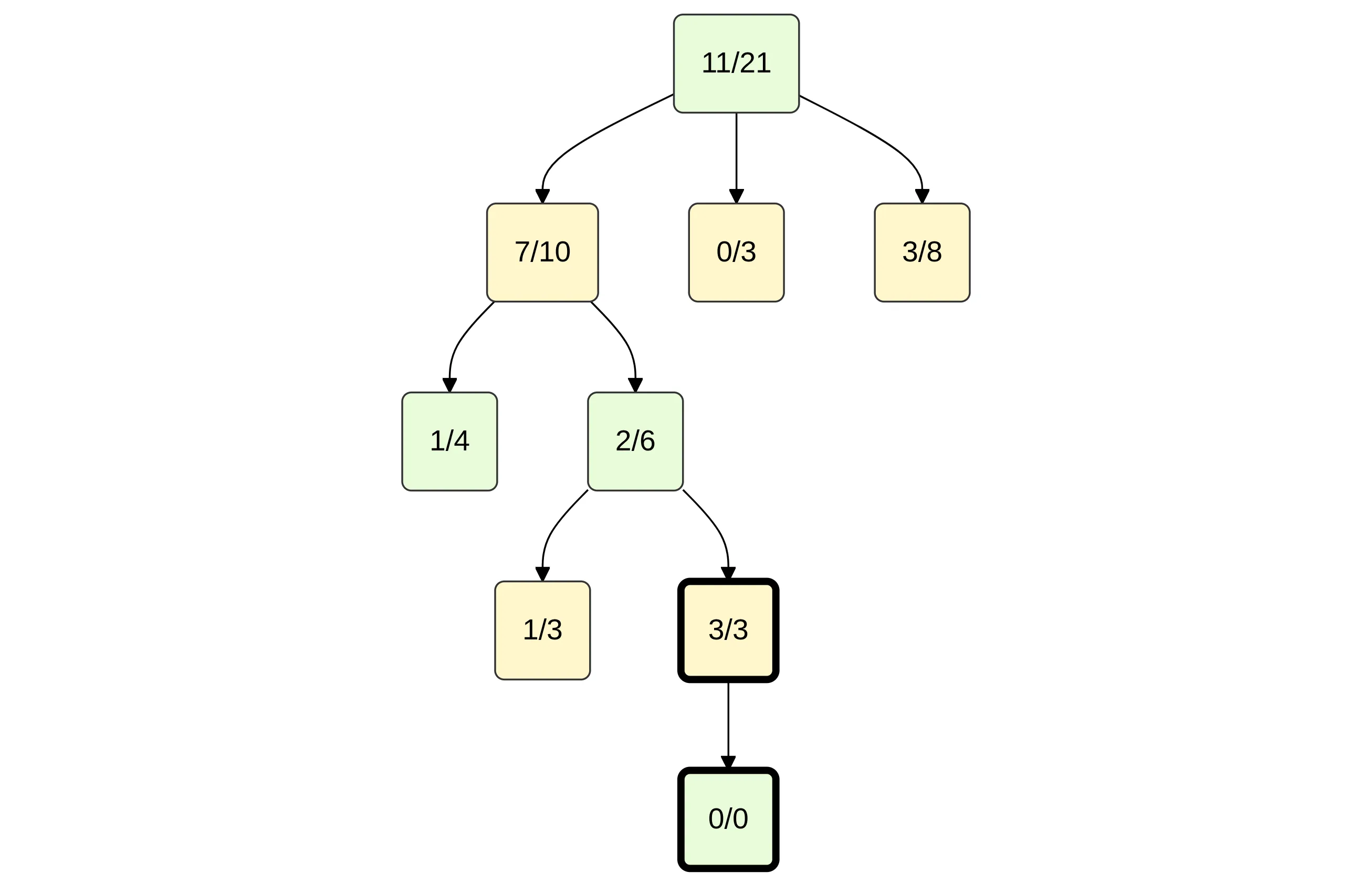

The illustration shows a simplified game tree processed by the Minimax algorithm with alpha-beta pruning. The goal is to determine the best move for the MAX player. Red nodes represent branches that the algorithm skips because they cannot influence the final decision.

The algorithm begins at the root (MAX) and fully explores the left branch, discovering a temporary best score of 6 (α = 6).

When processing the middle branch, the MIN player can force a value no higher than 5, which is already worse than the known α = 6. Because MAX would never choose this line, all remaining nodes in that branch are pruned.

A similar situation occurs in the right branch. After evaluating the first path, MIN can guarantee a value of 2, again worse than α = 6, so the rest of that subtree is skipped as well.

Alpha-beta pruning saves a large number of unnecessary evaluations without changing the final result. The final value returned by the algorithm is 6, the best achievable outcome for MAX assuming optimal play on both sides.

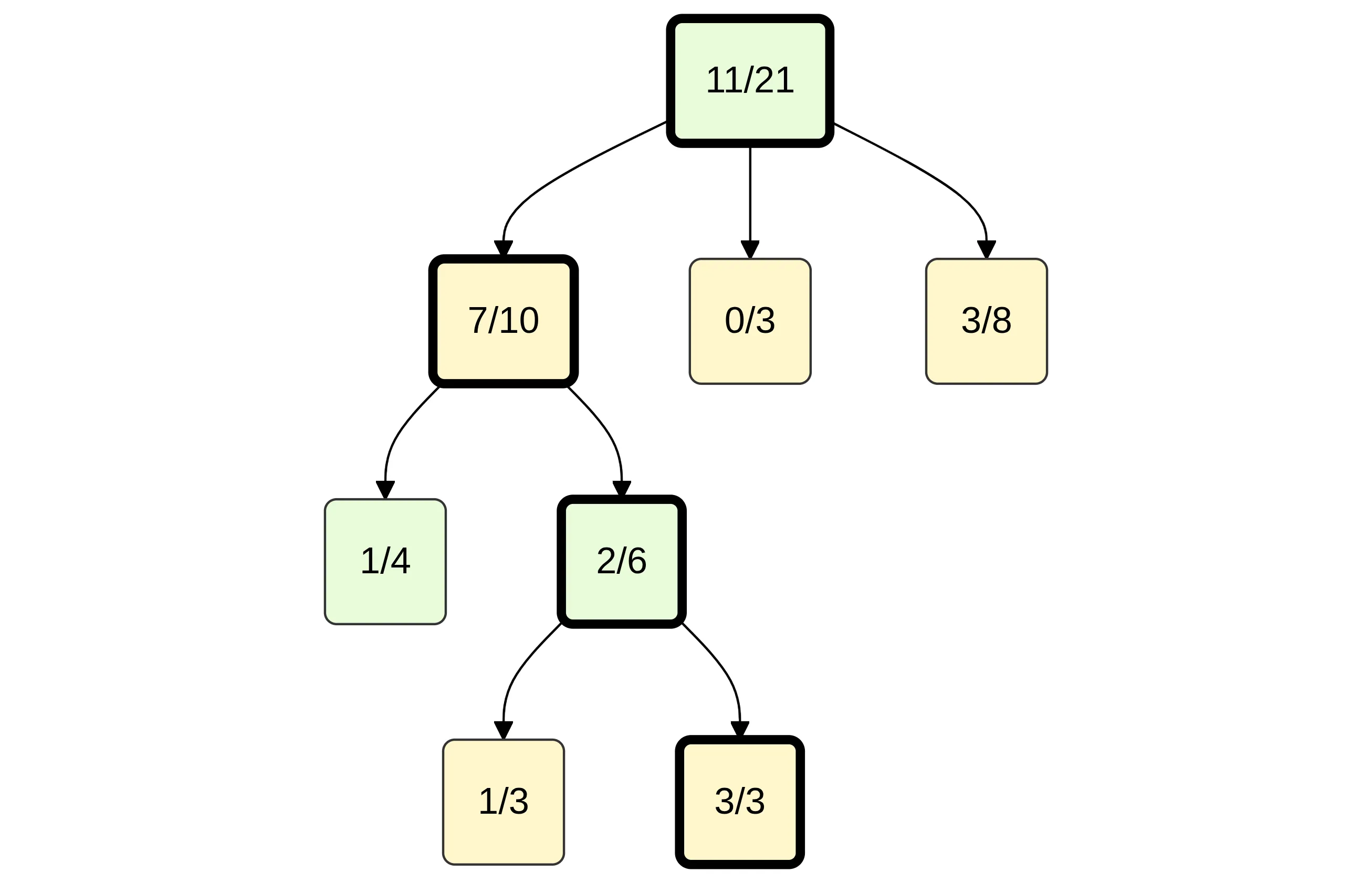

Best-First Search - Monte Carlo Tree Search#

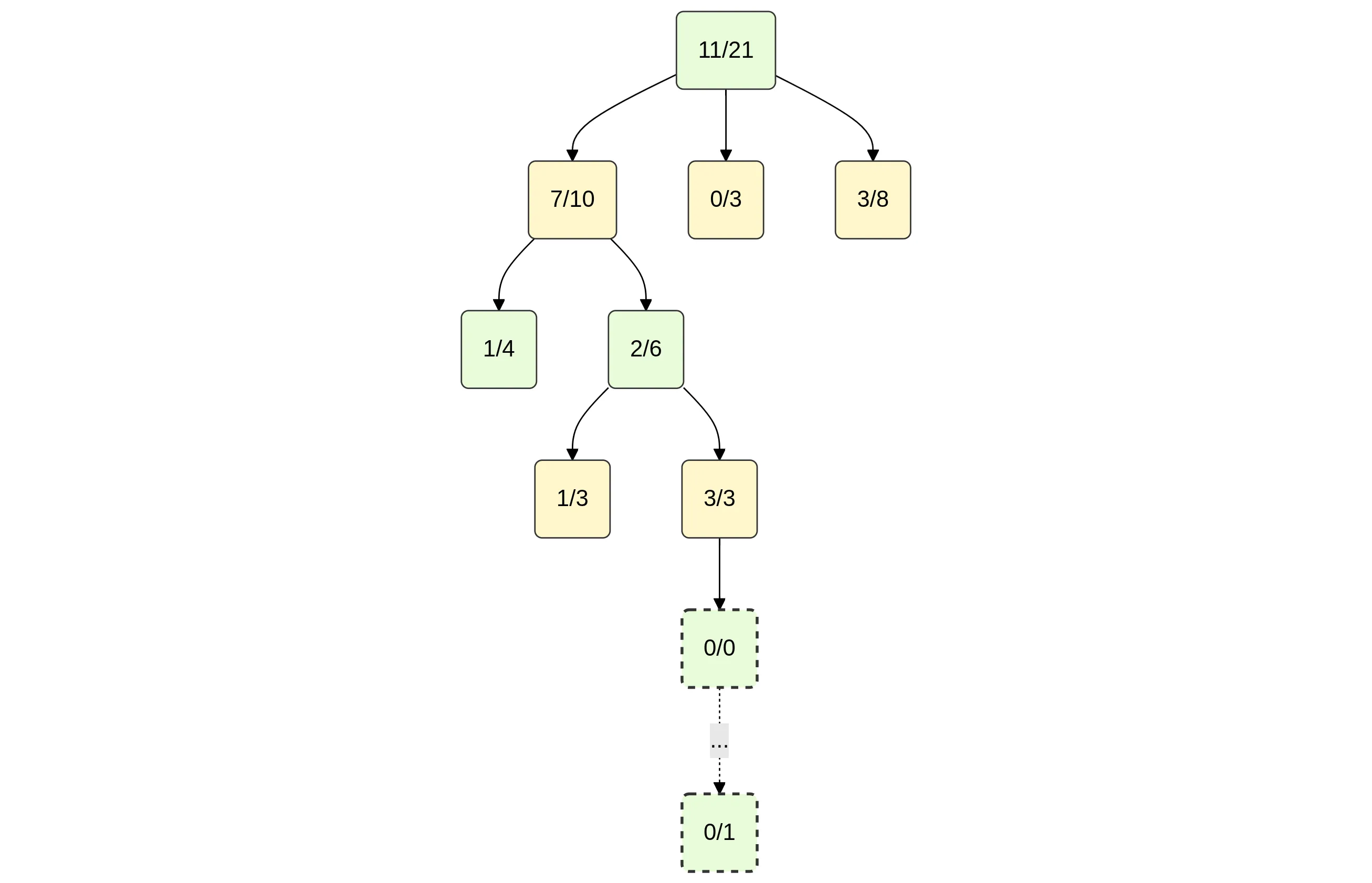

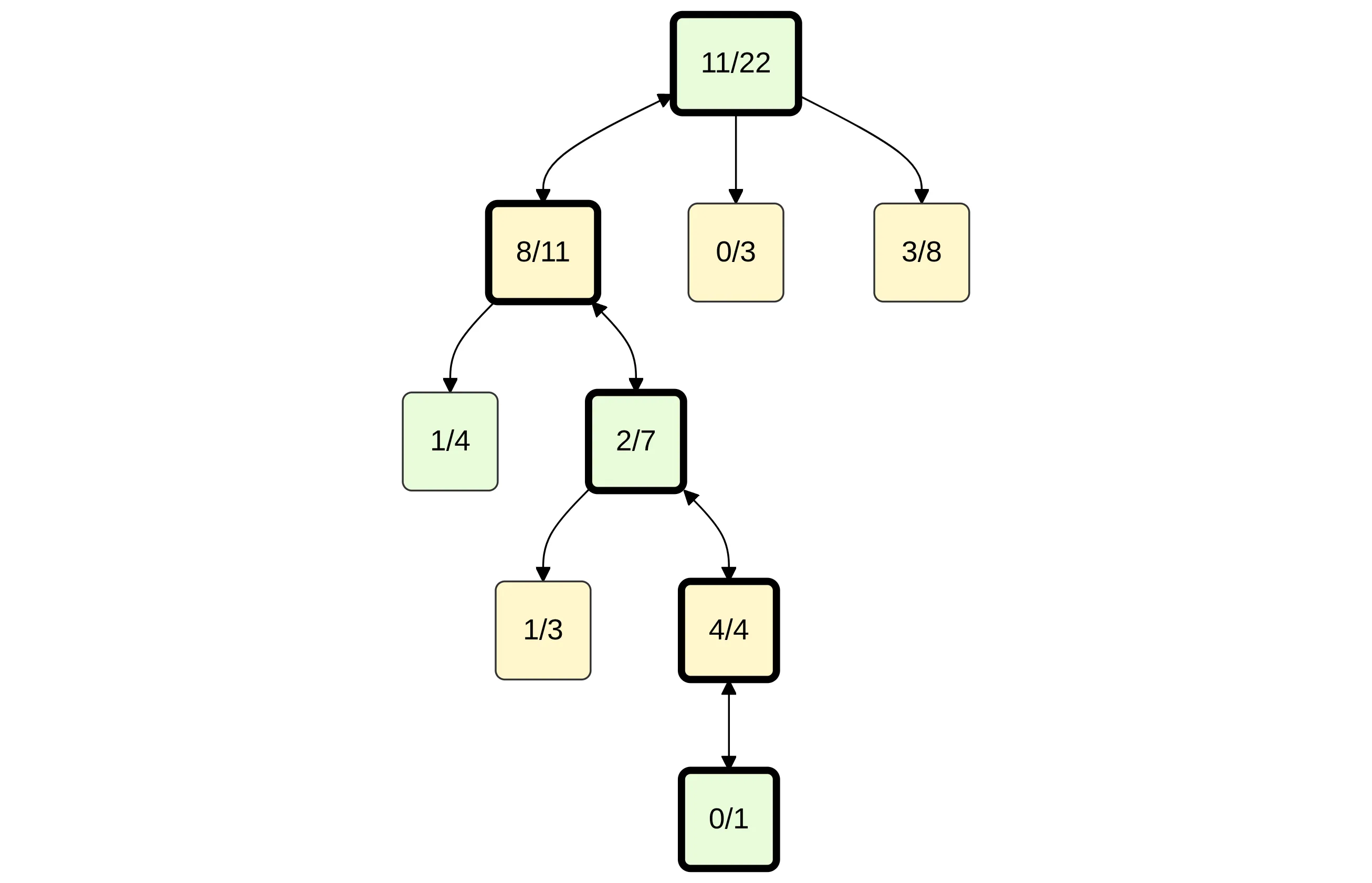

The next illustration presents a single iteration of the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm, which operates in four phases:

-

Selection

Starting from the root, the algorithm recursively selects the most promising child using the UCT formula, balancing exploration and exploitation.

In the example, the algorithm follows the path: root → 7/10 → 2/6 → 3/3. -

Expansion

Upon reaching a non-terminal leaf that is not fully expanded, the algorithm adds a new child node representing an unvisited move (shown as node 0/0). -

Simulation

From the new node, a full game is simulated until completion.

In the example, the simulation results in a loss for the player whose perspective is being evaluated (recorded as 0/1). -

Backpropagation

The simulation result is propagated up the tree.

Each node on the path to the root updates its visit and win counters:

0/1 → 4/4 → 2/7 → 8/11 → root 11/22.

Through this process, MCTS gradually learns which branches of the search tree are promising, improving decision-making in subsequent iterations.

Summary#

This work analyzed multiple search algorithms for universal board-game agents and evaluated their performance in a controlled environment.

Key conclusions:#

- PVS and Scout are the strongest classical algorithms for chess-like games.

- Transposition tables and quiescence search provide the best cost-to-benefit improvements.

- MCTS effectiveness heavily depends on simulation quality; naive random playouts are insufficient.

- The developed engine forms a modular foundation for future AI research in board games.

Future Work Directions#

- Improving MCTS with heuristic-guided or rule-guided simulations

- Integrating neural evaluation functions (deep networks, phase-dependent scoring)

- Using recorded games to build domain-knowledge datasets

- Automatic opening book generation

- Extending the engine to additional chess-like games

- Designing universal feature-based evaluation rules