CanSat

A high-school engineering project where we built a miniature satellite inside a soda can-from electronics and sensors to the flight computer, and recovery system. Our four-person team developed all software and hardware ourselves, gaining early hands-on experience with full end-to-end engineering.

- Side Project

- Java

- Python

- PyTorch

- Raspberry Pi

I Believe I Can Land#

My First Engineering Project (CanSat 2019)#

In 2019, just as I entered high school, I joined a small team that decided to take on the CanSat competition-an international challenge where students design, build, and launch a miniature “satellite” the size of a soda can. Even though CanSats don’t go to space, they’re deployed from ~1 km altitude and must perform real scientific and engineering missions: gather measurements, transmit telemetry, survive landing, and accomplish a self-designed secondary mission.

This became one of my earliest-and most defining-technical projects. It combined software, electronics, mechanics, physics, and a huge amount of trial and error. Our team called the project “I Believe I Can Land.”

Team & Roles#

We were a small group of four students, supervised by our IT teacher.

Although we initially divided responsibilities into clear roles, in practice everyone ended up doing everything-coding, testing, wiring, designing, and fixing whatever broke (which was often). It was true hands-on teamwork.

-

Lead Software Engineer - Krzysztof Zbudniewek

Built the full software stack: firmware, Raspberry Pi software, and the ground station. -

Lead Electrical Engineer - Bartłomiej Jacak

Designed the electrical system, wiring, and the integration of all modules inside the tiny CanSat cylinder. -

Lead Recovery System Engineer - Bartłomiej Krawczyk (me)

Responsible for modeling, testing, and designing the parachute system, including attempts at a guided parafoil. -

Software Engineer - Mateusz Kwiatkowski

Involved in developing firmware for the payload. -

Team Supervisor - Anna Stopińska

Oversaw the project and helped us navigate the competition requirements.

We were a small team-but motivated, curious, and very inexperienced. This project became our crash course in real engineering.

Mission Objectives#

Every CanSat must complete a primary mission and a self-designed secondary mission. Our secondary mission was ambitious-far more ambitious than we realized at the time.

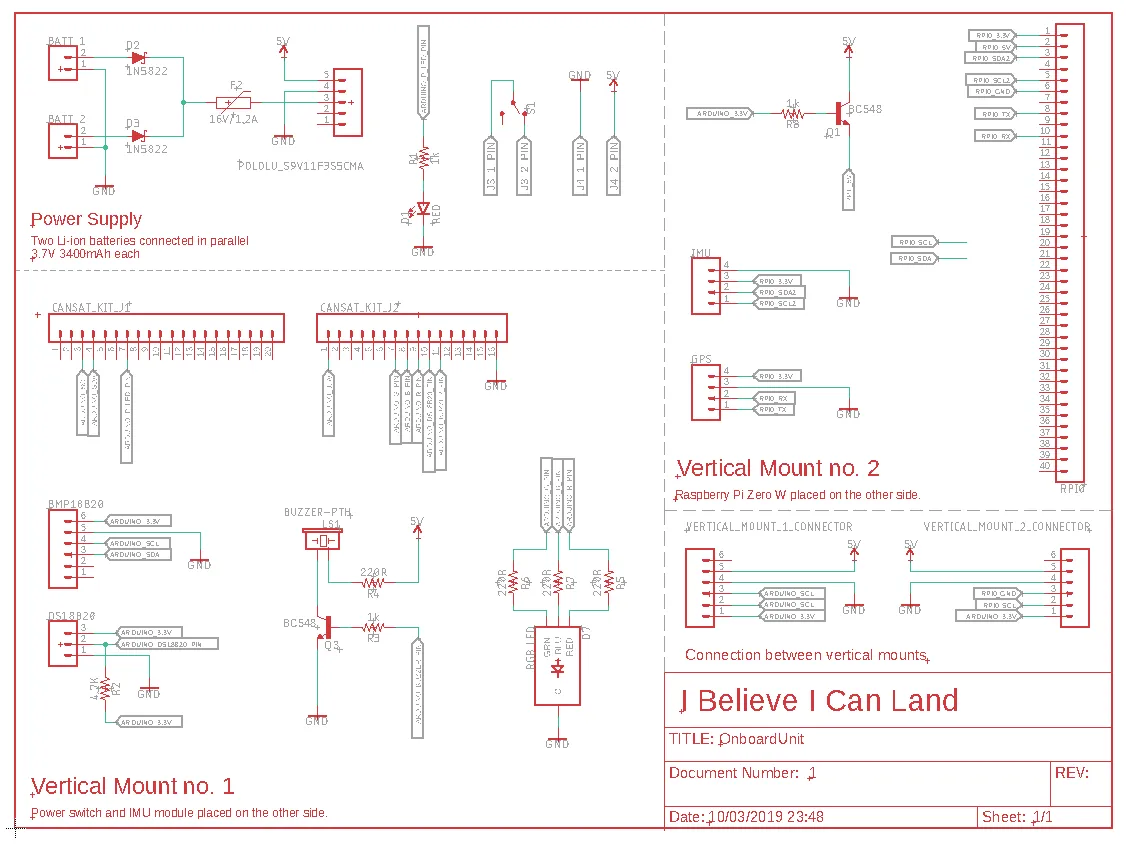

1. Primary Mission: Telemetry & Environment Data#

The CanSat needed to measure:

- temperature (DS18B20 sensor)

- static pressure (BMP280 sensor)

- flight altitude

- frame number / timestamps

Data had to be sent live to the ground station via an ATSAMD21G18-based microcontroller and stored on an SD card for post-flight analysis.

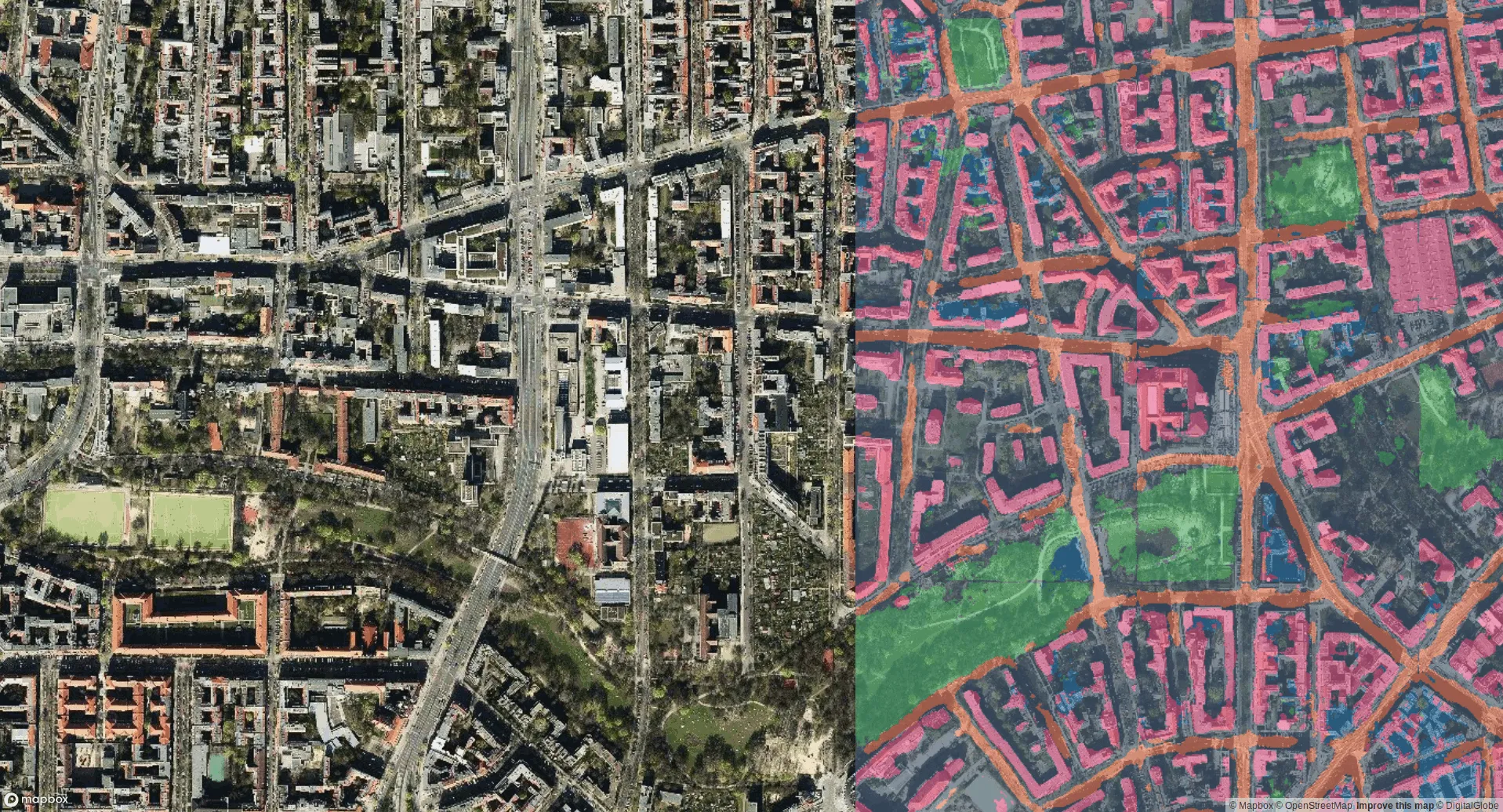

2. Secondary Mission: Real-Time Landing Site Classification#

Our bold plan was to classify terrain beneath the CanSat during descent to detect areas that were:

- safe (fields, grass, open terrain)

- unsafe (water, buildings, roads, forests)

We used:

- a Raspberry Pi Zero

- Pi Camera

- a convolutional neural network (CNN) built in PyTorch

The idea was to:

- Capture live images during descent

- Filter out blurry or tilted images using IMU data

- Correct the perspective

- Run them through a neural network

- Build a heat map of suitable landing areas

It was an early exposure to computer vision and embedded ML-long before “edge AI” became mainstream.

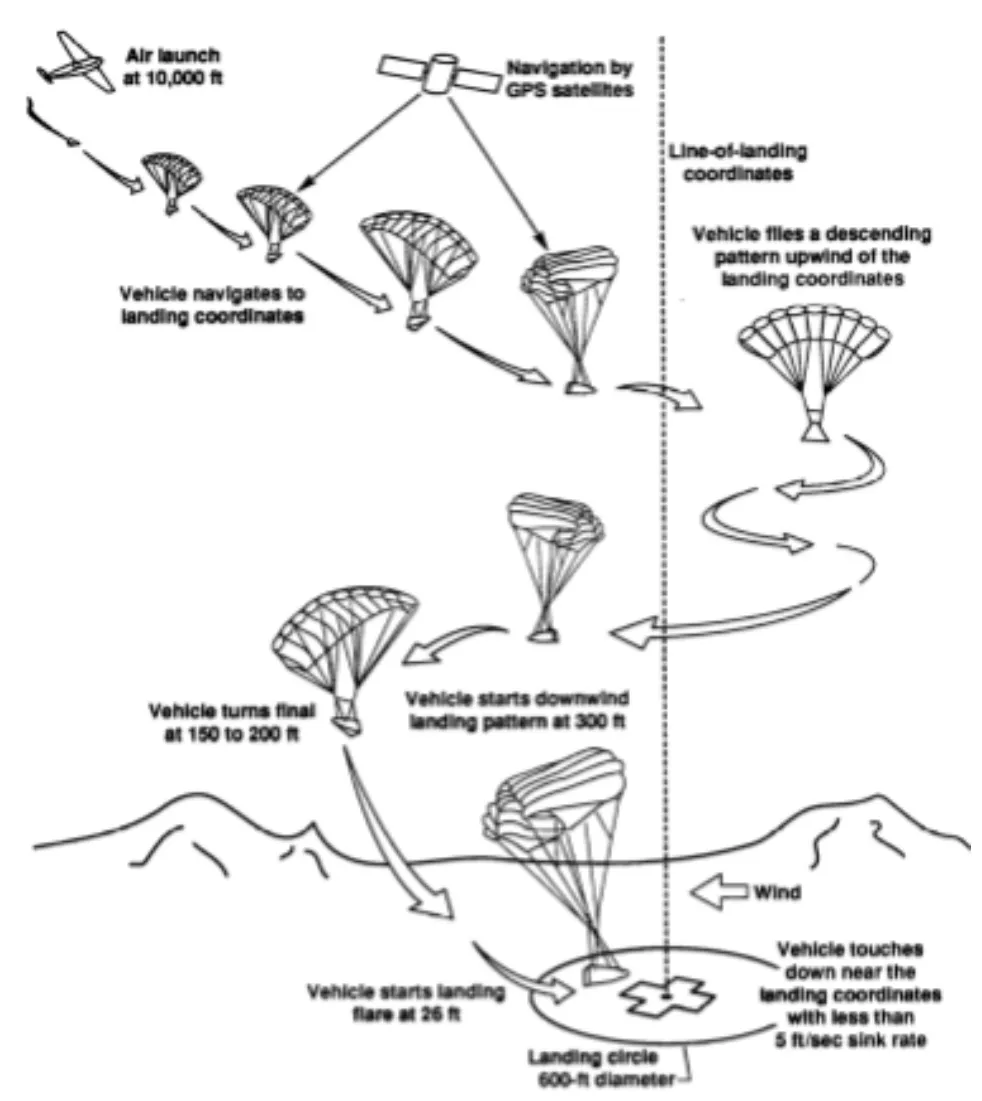

3. Attempted Tertiary Mission: Guided Landing#

Initially, we even wanted to steer the payload toward the best landing site using a parafoil parachute controlled by servos. This required:

- modeling lift-to-drag ratio

- calculating stable glide paths

- designing multi-line parafoil control

- simulating wind influence

While the idea was scientifically solid, reality reminded us that engineering is hard. After multiple failed prototypes (and many tangled parachutes), we ultimately dropped the guided-landing functionality and switched to a reliable round parachute.

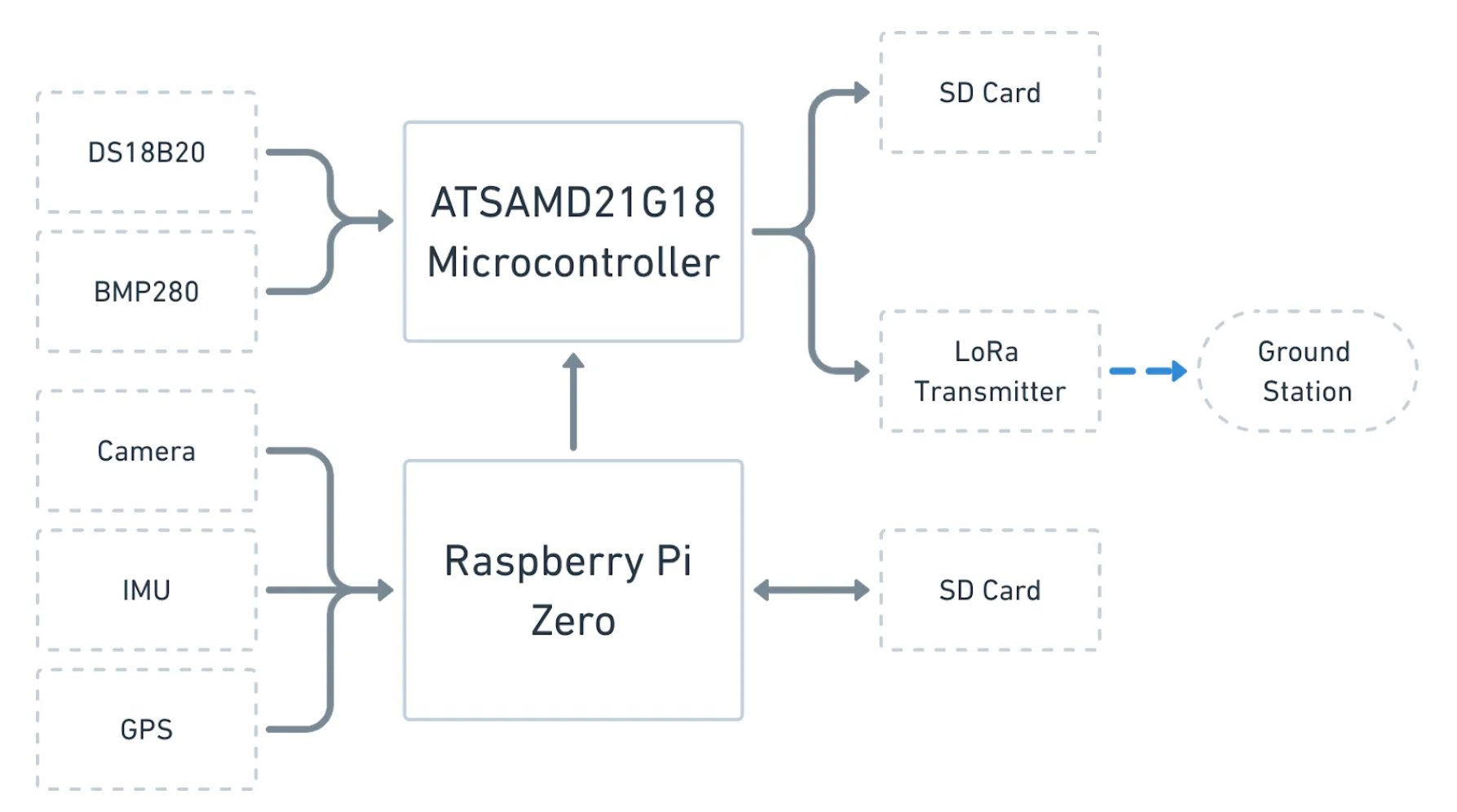

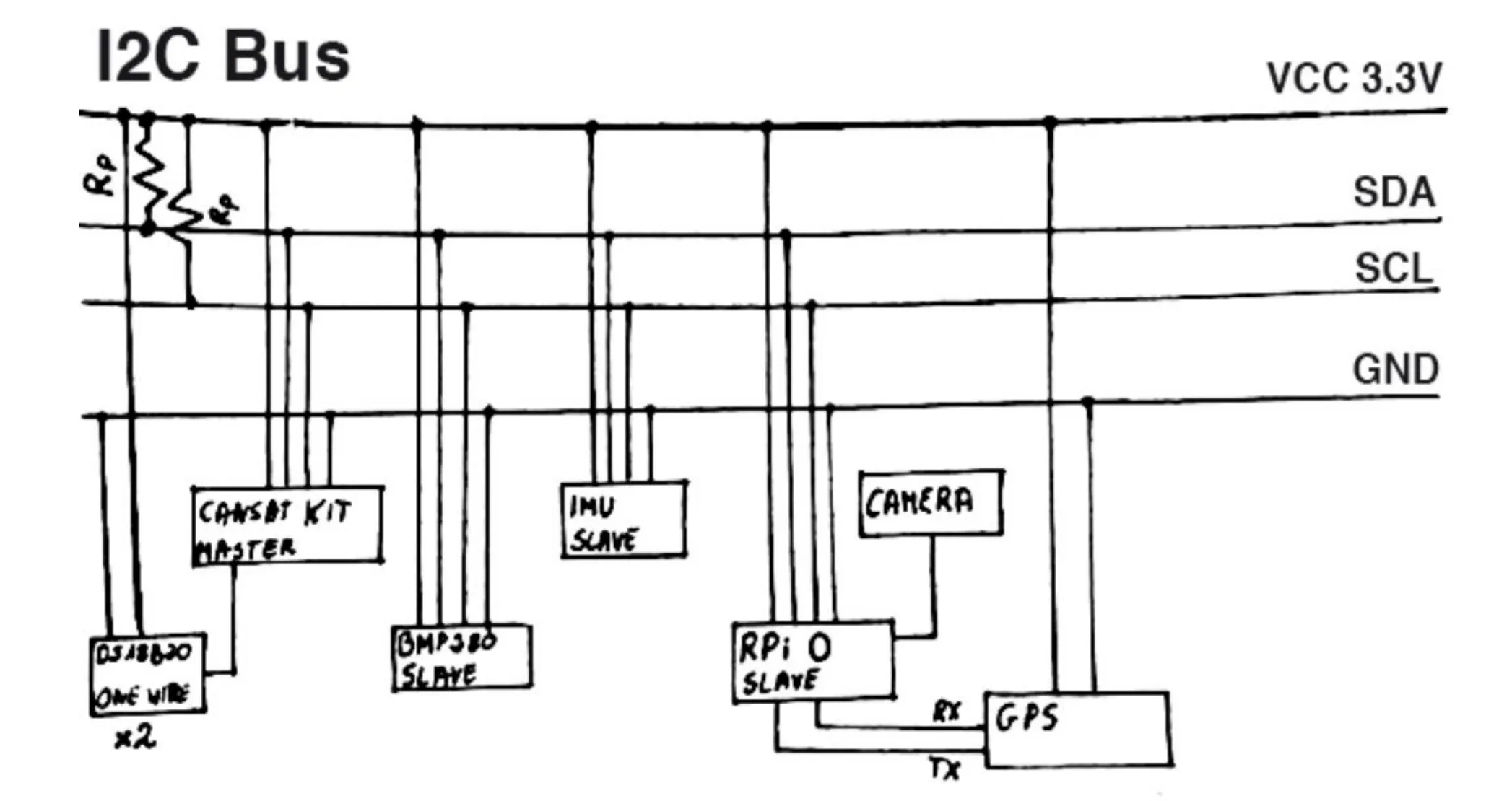

System Architecture#

Our CanSat was effectively a two-computer system:

Microcontroller (ATSAMD21G18)#

- Reads temperature & pressure

- Sends telemetry every second via LoRa

- Stores data on microSD

- Runs the entire primary mission independently

Raspberry Pi Zero#

- Captures images

- Processes IMU + GPS data

- Runs terrain classification (CNN)

- Generates landing heat maps

- Coordinates all secondary mission logic

The Pi communicated with its peripherals using:

- I²C for sensors

- UART for GPS

- Camera ribbon for PiCam

- SPI / SDIO for storage

Despite the tiny form factor, it was a surprisingly complete embedded system.

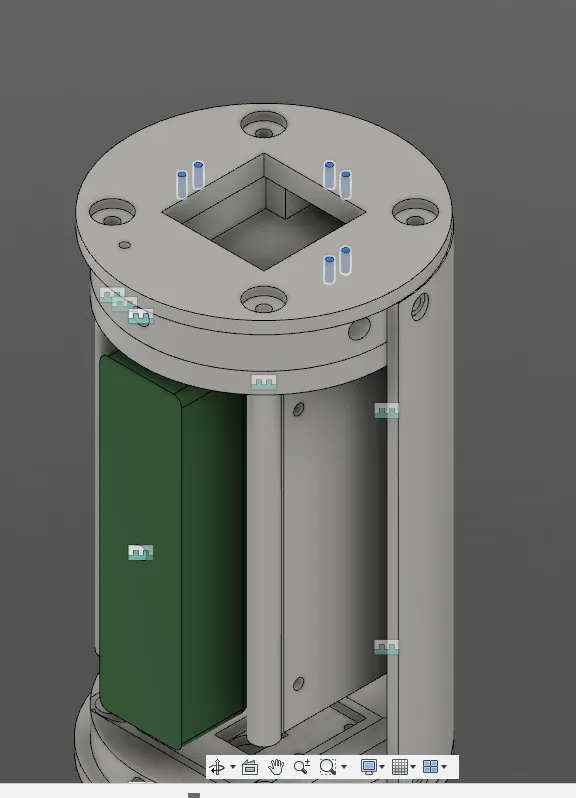

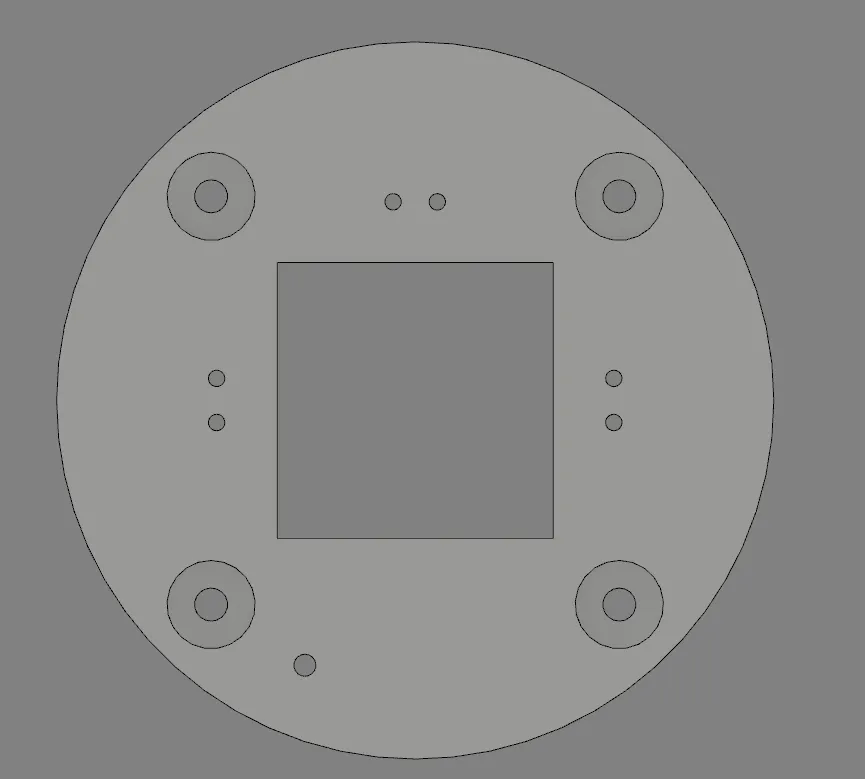

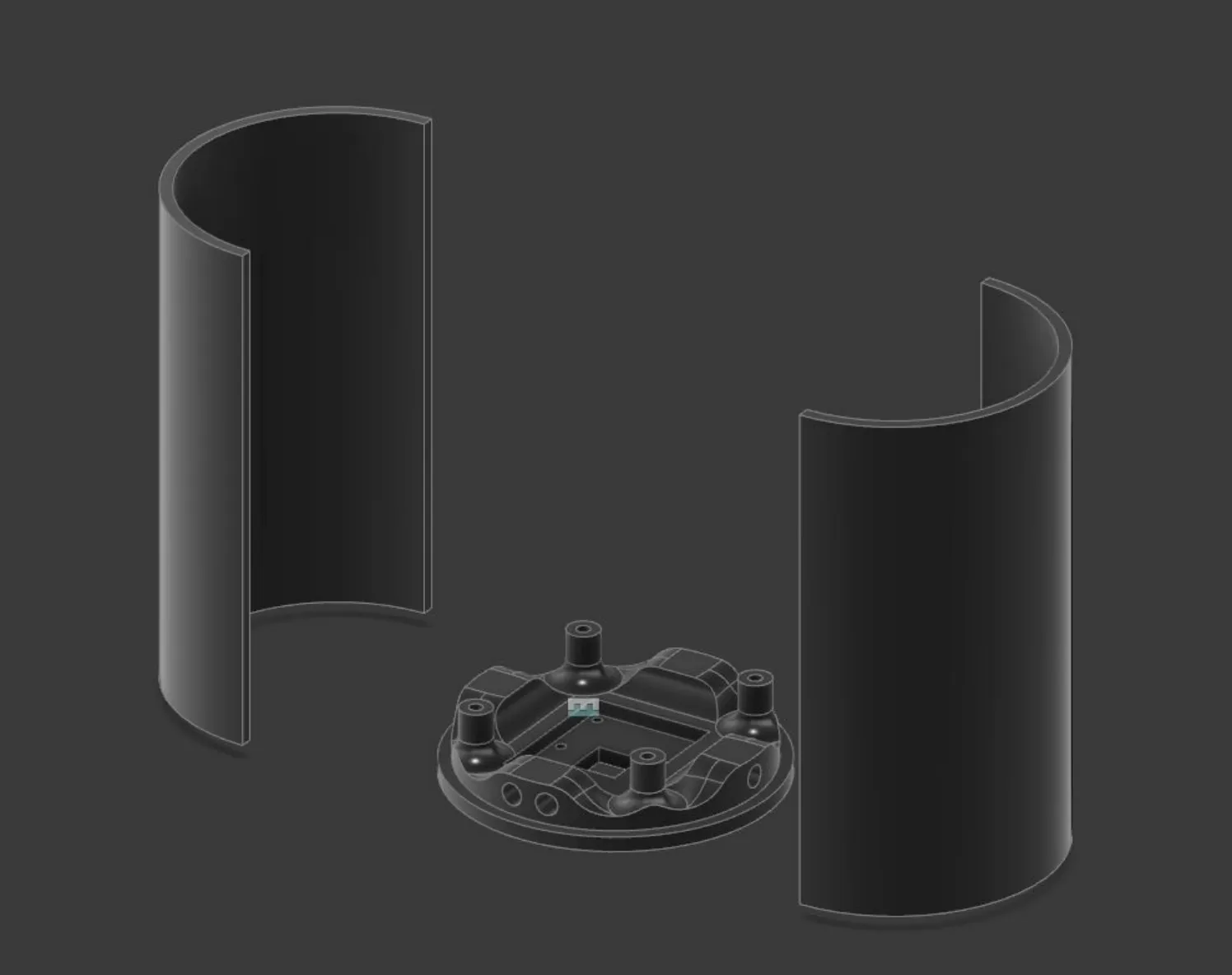

Mechanical Design#

Fitting a Raspberry Pi, camera, parachute mount, servos, and a full power system into a soda-can-sized shell was a miniature engineering challenge.

CanSat Case#

Designed in Autodesk Fusion 360, our case used:

- top and bottom plates

- 4 vertical guiding rods

- 6 external mounting holes

- 3D-printed internal supports

This modular design allowed fast inspections and repairs-something we quickly learned was essential.

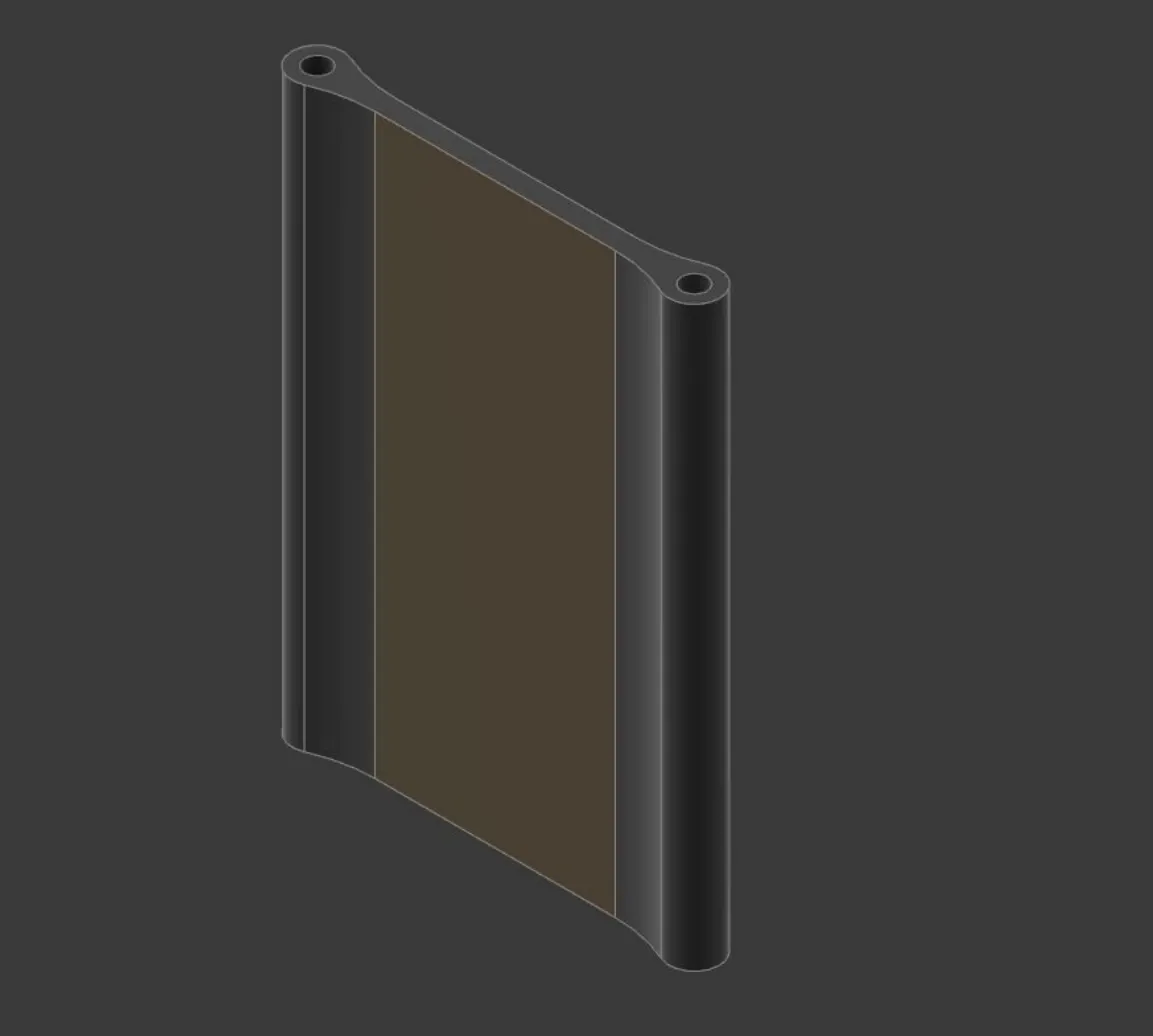

Vertical Mount for Raspberry Pi#

We created a dedicated 3D-printed vertical frame to hold the Pi Zero and extension boards. Given the tiny footprint and strict volume limits, this was the only feasible orientation.

Recovery System Engineering#

This was my part of the project-and the steepest learning curve.

Prototype 1: Parafoil (Clark-Y Profile)#

Our first goal was to build a controllable parafoil with:

- non-zero lift-to-drag ratio

- left/right steering via servos

- predictable glide performance

We built it from nylon fabric with household strings as suspension lines. It deployed-but didn’t glide. It simply descended like a normal parachute.

We realized we had incorrectly adapted round-parachute formulas to a parafoil, which behaves completely differently aerodynamically.

Prototype 2: Parafoil (Based on Academic Research)#

We rebuilt everything using aerodynamic equations from:

- Om Prakash, Aerodynamics, Longitudinal Stability and Glide Performance of Parafoil/Payload System

This time we:

- adjusted aspect ratio

- optimized chord length & canopy span

- changed line thickness to 0.2 mm

- recalculated lift/drag forces

The updated parachute flew much better-but had problems:

- too large for the CanSat container

- inconsistent openings

- frequent line tangling

- delayed inflation

Ultimately, we determined the design wasn’t reliable enough for the competition constraints.

Final Design: Round Parachute#

Based on NASA and CanSat training materials, we switched to a round parachute-simple, reliable, predictable.

And most importantly: it fit inside the can.

Testing the System#

We tested each subsystem separately before integrating:

Primary Mission Tests#

We verified telemetry accuracy by reading:

- frame number

- pressure

- temperature

Comparing DS18B20 and BMP280 validated sensor accuracy.

Secondary Mission Tests#

Testing the parafoil prototypes took weeks:

- balcony drops

- school-building drops

- indoor glide tests

- multiple redesigns

While the neural network prototypes worked in simulation, real airborne testing was limited by our parachute delays.

Project Timeline & Iterations#

Between November 2018 and March 2019, we built:

- 4 main hardware prototypes

- 3 parachute generations

- 2 software stacks

- dozens of drop tests

- a full outreach program (blog, shirts, presentations)

It was more than a school project-it was a full engineering cycle.

Budget & Sponsors#

Total budget: ~500 PLN (~116 EUR) Most parts were sponsored by:

- TPU Sp. z o.o.

- BOTLAND (discounts and support)

Outreach & Public Engagement#

We documented the project with:

- a Facebook page

- technical blog posts

- school presentations

- visual branding & logo design

- even an article in local newspaper

It was a great introduction to communicating engineering work publicly.

Conclusion: What I Learned#

This project taught me more than any class at the time:

- how to work in a team

- how to design, test, and iterate hardware

- how to integrate software with real sensors

- how to model aerodynamic systems

- how to manage complexity under tight constraints

- how to fail, recover, and move forward

“I Believe I Can Land” was my first real multidisciplinary engineering experience. It sparked my interest in embedded systems, physics-based modeling, and designing things that interact with the real world-a theme that continues in my later projects.